Also a Doctor of Geography and coordinator of Slow Food France, he explains to us how food that is good, clean, and fair contributes to the restoration of ecosystems and the empowerment of indigenous peoples.

Can you introduce us to Guayapi and its values?

Guayapi is a commercial company founded by my mother, Claudie Ravel, in 1990, whose mission is to select and promote plants harvested from the wild in the Amazon and in Sri Lanka. We are a family business celebrating its thirtieth anniversary this year, with a team of twelve people in Paris. We adhere to three fundamental criteria: organic agriculture, fair trade, and biodiversity restoration.

What products do you offer?

We present these plants in three categories. Dietary supplements or superfoods, such as Warana (the name the Sateré Mawé Indians give to guarana), maca, or camu camu for example. Natural cosmetics, and gourmet grocery items. These products are distributed through a network of 3,000 specialty, organic and fair-trade stores.

Among your core criteria is fair trade — how do you put that into practice?

We have had a flagship project since 1993, the Warana Project. Within our means, we support the Satéré Mawé Indians, a people from the central Brazilian Amazon. There were 6,000 people at the start of the project, and there are 18,000 today!

This people is determined to self-manage, notably through the Consortium of Sateré Mawé Producers, with whom we work and from whom we buy Warana directly. It represents 337 producer families.

What is Warana? How is it different from guarana?

This is the same plant, the sacred plant of the Satéré Mawé Indians. Warana is the traditional name. It means “the principle of knowledge” in their language, and it is a protected designation of origin in Brazil. It is a powerful physical and mental energizer that is not overly stimulating, which Guayapi brought to market as early as the 1990s, alongside other plants that the Indians offer today, because they have diversified their cultivation.

Slow Food, the movement I will talk about later, recognizes our Warana as a Sentinel: a food to be preserved against the threat of the soda industry, which uses guarana.

Were you talking about wild foraging?

Yes, we do wild foraging, in what are called forest gardens. I’ll give you an example. In Sri Lanka, we are partnered with a family on an eco-tourism project. It involves 20 hectares of land in the central mountains that used to be a tea monoculture. It should be noted here that tea was introduced to Sri Lanka by the English. It’s a colonial product! We restored the original ecosystem with ecologists and obtained the certification we use for our products, FGP “Forest Garden Products”.

This label guarantees not only organic origin and the socioeconomic criterion of fair trade, but also the well-known biodiversity criteria I mentioned at the beginning. In our view it is the most comprehensive certification worldwide, because you should know that today there are almost 400 organic certification bodies. But when it comes to biodiversity, it is much more difficult to find the necessary expertise!

How do you manage to restore the biodiversity of the ecosystems where you harvest the plants?

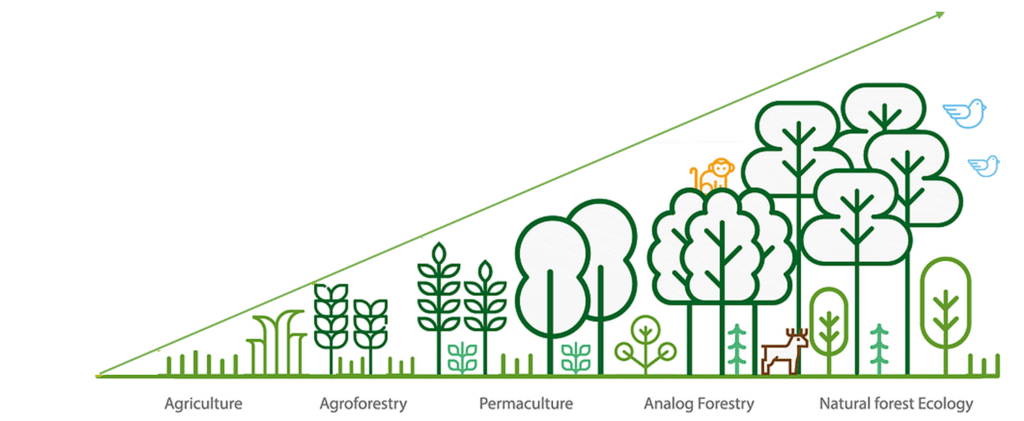

As I was telling you, our project in Sri Lanka is a former tea monoculture. We restored the degraded ecosystem using the analog forestry technique (Analog Forestry in English), conceptualized and put into practice from the 1980s by system ecologist Dr. Ranil Senanayake.

The goal is to restore ecosystems by imitating the forest and nature. It is a form of silviculture that mimics the ecological functions and architectural structures of original mature forests. It is the most advanced method! It has existed for 40 years in Sri Lanka and is now being implemented on all continents.

How long does it take to restore an ecosystem with analog forestry?

In an analog forest design, after only 7 years the ecosystem begins to act like a forest in terms of ecosystem services — that is: oxygen production, carbon sequestration, micro-habitats for animals, water purification, etc. And after 15 years, you already have a system that behaves like a mature, stable forest (what is called the forest’s climax state).

What nature would take more than a hundred years to restore on its own, analog forestry achieves in just 15 years. It’s visionary!

Because of the fires, the Brazilian Amazon has seen its worst June in 13 years. In your opinion, what are the main causes of deforestation in the Amazon?

For me there is a triple threat. First, the threat of agro-industrial capital: it is the primary cause of deforestation in the Amazon. We convert the forest into monocultures, to the point that today 25% of the forest is affected.

Secondly, the current Bolsonaro government. It has further unleashed and intensified these external aggressions and territorial invasions. And it is openly anti-Indigenous.

Third, we are seeing COVID-19 reach the Amazon. In Brazil, the epidemic is completely out of control. Manaus, the capital of the state of Amazonas, is the second hardest-hit city in the country. The virus is reaching communities. Among the Satéré Mawé Indigenous people, there are already deaths, and the situation is very, very serious.

A question consumers should ask themselves: does developing these analogue forest projects offset the carbon footprint of a food item that comes from far away?

Indeed, it’s a question we’re often asked. “The carbon footprint”, to begin with, is a rather vague concept. But clearly, the environmental or even social quality of a product does not necessarily have anything to do with whether it is local or not. You can quite easily buy French products close to home that are produced and manufactured in deplorable conditions! Conversely, the Analogue Forest sequesters far more CO2 than transportation can emit.

For me, it’s a mistake to think that local is necessarily better. I’m being provocative in saying that, but that’s exactly what the National Rally proposes!

Consuming French-only or strictly local products is dangerous at its core: culture and intangible wealth depend above all on exchange and mixing, and it’s important to remind people of that here, because today there are excesses. It comes from good intentions: people are questioning how they consume and can be anxious about territorial decline.

Of course, we must rebuild our local communities, support our producers (women and men), and rediscover seasonality. But we must not respond to this fear with an exclusively localist answer or by closing in on ourselves.

The challenges are global now, and Europe also has a historical responsibility for colonization. Today we have food products, animal or plant, that are cleaned or processed in the Maghreb, then packaged in Eastern Europe, before being resold in France. Examples of ‘local’ products whose processing is completely internationalized: shrimp, tomatoes, hybrid seeds, meat from industrial slaughterhouses… That is what we must fight against. And not good, clean, fair products that support Indigenous peoples of the Americas.

So is production more polluting than transport?

Transport accounts for 10 to 12% of greenhouse gas emissions. That’s as much as the digital industry. It’s an interesting paradox that we use social media to denounce products that come from far away through a channel that pollutes just as much!

The aviation industry accounts for only 2 to 3% of greenhouse gas emissions. Agriculture and industry account for at least 40%. It’s the largest source of pollution! These figures come from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

The pollution from products depends less on distance — local or global — than on how they are produced.

For foods that come from far away: if they come from monocultures, it’s catastrophic. If they’re products that can be substituted by products that come from here, that’s pointless too. But when we have products grown in forest gardens, which store a huge amount of carbon, that’s a good thing. For example, a tree in a forest can store up to two tons of carbon per year. One hectare of preserved primary forest in the tropics can store up to 400 tons of CO2 per year.

If the product is well made, good (for the palate and health), clean (for the planet) and fair (for the producer), like Warana, packaged in eco-friendly materials, the transport is largely offset.

There is also the question of seasons and the scale of supply chains…

In terms of seasonality: I love superfoods from around the world and I also love local products made by small European, French, and regional producers, and above all seasonal ones.

And it’s not incompatible: superfoods from around the world complement our diet with their flavors and benefits, enriching our dietary habits and our gastronomy. Cinnamon, pepper, noble cacao, warana, açai, camu camu… are also important nutritional sources.

And what also matters is the scale of the supply chains. At Guayapi we run short supply chains internationally. We buy Warana directly from the Consortium of Sateré Mawé Producers (representing 337 families of Sateré Mawé Amerindian producers). It should be remembered that geographic proximity does not mean the supply chain is short!

Do you think the rise of environmentalists in the municipal elections will concretely change things?

This is very good news! We also see the difference in the European elections, there is a green wave and it’s a deep societal trend that is shaping the planet’s future.

There are two levels of politics in my view. There is party politics, which means we vote every five years. It’s an old-fashioned view of politics. It has its place, it’s legitimate, but there is also, in my opinion, politics in the noble sense, with a capital P.

Every day, each of our actions is political: we vote three times a day by choosing what we eat!

You are co-President of Slow Food Paris-Region, can you tell us about the Slow Food movement?

Slow Food is a major food movement born in Italy thirty years ago and now present in 170 countries. It was founded in reaction to Fast Food. The idea is to defend food that is good, clean and fair, as I told you.

We also defend food biodiversity with various programs, a network of sustainable chefs, small farmers, academics… We carry out many actions and campaigns worldwide. This would merit another interview, because this movement is not well known in France! Everyone is welcome to join us!

How do you envision food in the future?

It’s a very difficult question; I couldn’t pretend to know how we will eat in the future. What would be best is to follow the same values as Slow Food: adopt a slow, fair diet that meets nutritional needs, respects the planet and avoids waste. Fair food for everyone.

For me, it will be very important to restore food to its rightful place at the center of society, while respecting the regions and their ecosystems. Agricultural production today is indecent and creates an enormous amount of waste. I also believe that agricultural land should be reallocated to the restoration of original ecosystems.

In the future, we will still need urban spaces, but far fewer than today, and they should be much greener and more naturalized, with projects for urban forests and community gardens that create social ties, jobs, and oxygen.

Next, we should have agricultural zones aimed at equitable food supply as I mentioned; a few areas will be needed for silviculture (tree plantations for paper, for example)… But I believe that most of the land should be allocated to the restoration of original forests through analogue forestry, with the sole purpose of restoring ecosystems that are vital for humanity. Forests and rich soils are, after all, our life-support systems!

An objection that could be raised: how can we feed 8.8 billion people in 2100 while reducing agricultural land?

Once again, this is a question that is unfortunately biased by agro-industrial propaganda. Today we waste between a third and half of the food we produce globally. That represents 1.3 billion tonnes each year according to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

A third, or even half, of the food we produce doesn’t end up in someone’s stomach but in the trash!

The narrative that we must produce more to feed more people is a myth invented by agro-industrial companies to sell more GMOs and supposedly develop more efficient techniques. Today we have enough on Earth to feed 9 billion people!

The Earth is generous enough to meet everyone’s needs, but it would not satisfy the greed of a single person.

There is a poor distribution of food resources and unequal access, including economic access. It’s not a problem of quantity at all but of quality and the structural allocation of resources. Education plays a major role: we must educate people about these issues so that, day to day, they make more conscious food choices.