Louise Browaeys cultivates the earth as she does words. This year she has three notable reference books, The Planetary Health Regimen, a Little Handbook of Punk Cooking, and an eco-feminist fable, The Dislocation. A discussion around topics close to our hearts: food, ecology, and feminism.

You are an author, permaculturist, agronomist, CSR expert… You seem to be active on several fronts and passionate about different fields; can you tell us about your background?

I was born near Nantes on the banks of the Loire, where my parents run a nursery. So I was immediately thrown into the deep end of the plant world! I grew up between a garden and a library, and my parents passed on to me this love of gardening and nature.

I studied agronomy [ at AgroParisTech ] and first worked in organic farming. I then discovered the world of organizations and worked in CSR for years. I linked an ‘organic’ approach to agriculture with an ‘organic’ approach to organizations, particularly through human permaculture.

I’ve been self-employed for three years now, and I work on what I call the three ecologies: inner ecology, relational ecology, and environmental ecology.

Are you the one who theorized these three ecologies?

Not really, there are a lot of people who claim it today! Originally, it comes from the philosopher Félix Guattari. Inner ecology refers to discernment and singularity, relational ecology concerns the connection to others, environmental ecology is the impact we have on the landscape.

I began writing at the age of 12, and I knew that writing would also be something important in my life. I first published essays on permaculture and ecology. Then I wrote cookbooks.

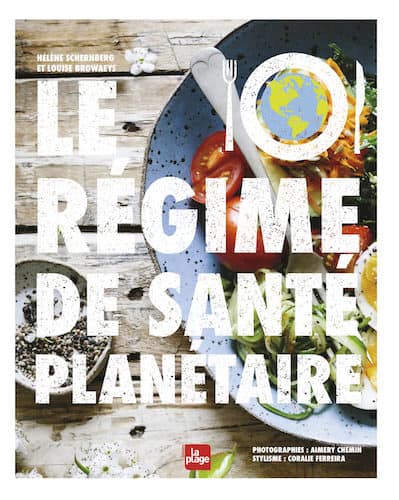

You have just published a book co-written with Hélène Schernberg, The Planetary Health Diet, published by La Plage. You recommend changing what we put on our plates for our health and the environment by 2050. Can you tell us more?

For The Planetary Health Diet, we started from a scientific study called the EAT-Lancet Report, which explains what we will now need to eat for our health and that of the planet. The link between the two is fairly easy to understand! The foreword is by Walter Willet, who is an American physician and nutrition researcher at Harvard University.

We really dissected that study! The idea was to translate a serious scientific argument into recipes, actions, and new practices. We talked about the food transition, provided figures and recommendations…

Increasing the proportion of plant-based proteins on our plates is fundamental. But we should also rethink our fats, develop raw and fermented foods, and increase the diversity of what appears on our plates.

I have two pet obsessions. The first is pleasure. “Pleasure is a form of production” says Bill Mollison, one of the founders of permaculture. And for me, pleasure in cooking is also very important. The second is accepting failure. In the book, we offer recipes that are very easy to make. Because seeing people on Instagram who succeed every time can be discouraging. And that, for the record, is a change in stance, so it concerns inner ecology.

This book — Hélène Schernberg and I are very proud of it, because we worked on it a lot. With I Cook Ecologically, published by Larousse, these are the two cookbooks I am happiest with!

What are the main recommendations of the planetary health diet?

I try not to frame things negatively. Regarding meat: there are a lot of negative injunctions, so you have to be careful. The recommendations are the titles of our chapters:

- consommer plus de fruits et légumes

- diminuer la viande et le poisson et surtout mieux les choisir

- redécouvrir les céréales complètes, consommer plus de légumineuses, plus d’oléagineux

- remplacer les oeufs ajoutés

- réduire sa consommation de lait et produits laitiers

- éliminer les sucres ajoutés, bien choisir les matières grasses et les produits transformés

- privilégier les produits locaux et de saison

- privilégier les modes de production durable

- réduire ses déchets et le gaspillage en cuisine (réutiliser les restes, manger les fanes..).

And we also presented the top 15 healthy foods and the top 50 foods of tomorrow. For these foods of tomorrow, we started from another particularly interesting study by WWF and Knorr, which selected those that have a lower ecological impact, good nutritional characteristics, that are accessible, that taste good, and that are accepted by consumers.

What are the current barriers to this planetary diet?

It’s about knowledge! People associate plant-based cooking with boring, not very good food because they don’t know it. What do you do when faced with a bag of lentils? For me that’s the barrier. Because when you know how to cook it—Indian-style or Italian-style, or like in the Middle East, with good oils, spices, herbs, and colors—it’s very good. There is a problem of unfamiliarity with how to cook vegetarian food so that it’s at once appetizing, tasty, and healthy.

When we talk about a “planetary” diet, are we addressing European populations or is it something that can be applied everywhere in the world?

We tried to be broad when talking about the objectives. These are recommendations that can be generalized. We are mostly referring to products that come from our local region, but all the main themes I have just discussed are transferable to highly industrialized countries, where junk food prevails.

In some less industrialized countries, reducing meat consumption doesn’t make sense for certain populations, because they already don’t eat that much of it. One must always take into account soil and climatic conditions, cultures, customs, needs, resources… These recommendations would need to be adapted to each country. The book is aimed more at a European context.

We often associate local agriculture with ecological agriculture. We discussed this return to locality with Bastien Beaufort, the director of Guayapi (a brand that promotes foods sourced from wild harvests in analogous forests in the Amazon and Sri Lanka). According to him, we can also have an ecological diet with foods that come from far away, insofar as their production methods allow carbon sequestration, offset their transport, and involve collaboration with small-scale producers.

I would not presume to judge this project, which I do not know. Yes, we should not cut ourselves off from certain foods that come from far away and that we cannot produce here.

Obviously, there are foods that come from far away and are a priority: coffee, cocoa, spices… Since we can’t grow them here, we need to work especially on these supply chains so that they are fair.

But buying kiwis that come from New Zealand when we have them in France seems absurd. Regarding quinoa, there are places where it is grown and sold fairly, but there are also places with serious excesses, where it unbalances the soil and family economies, because all of a sudden it becomes an export crop and local people abandon their subsistence farming. This is what Marcel Mazoyer and Laurence Roudart explain in History of World Agriculture, a very beautiful book!

To go back to quinoa, it is grown in France, in the Anjou region. I think I prefer to consume local quinoa rather than quinoa that comes from far away. It’s interesting to taste, to try new foods… But for some mass-produced products, no. I’m thinking of bananas, for example, the pollution they create locally and the transport they involve.

There’s a lot of talk about superfoods, but they don’t necessarily come from far away! I remember studying blackcurrants, prunes, all the superfoods we have here in nutrition class! We could do without chocolate but then we’d be directly addressing the principle of pleasure in cooking!

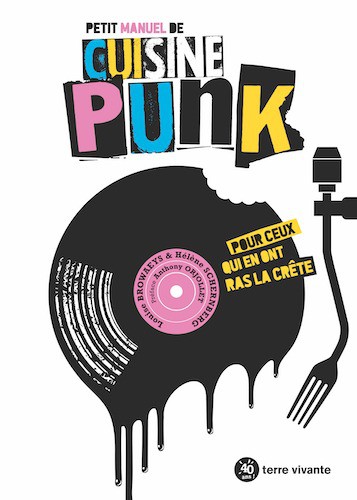

In the Planetary Health Diet, you offer concrete applications with lots of recipe ideas. You’ve already published around fifteen cookbooks, by the way, including one that has just come out on Punk Cooking at Terre Vivante editions. What is Punk cooking?

About this Little Handbook of Punk Cooking: it was about taking a new approach to talk again about alternative cooking, more plant-based, fairer, healthier…

One might think that punk cooking means eating beer and kibble, but no, it’s a return to Punk culture. That is to say, claiming an alternative cuisine, and no longer being on the somewhat “feminine”, “Instagrammable” side. We talked about anti-capitalist foods, the raw, the rotten…

There is a scientific article on punk cuisine that talks about the raw and the rotten, that is, the raw and the fermented. There are different aspects: rejecting consumerism, the domination of agribusiness and brands, salvaging and repurposing, respecting the planet, celebrating diversity, saving money…

There is a certain beauty in all of it. And also a very offbeat side: for example when you ferment your oat yogurts on your radiator.

And what role does cooking play in your life? Who introduced you to it?

That’s my mom. There are family recipes in my books! I’ve always loved cooking; I used to copy everything into my recipe notebook: recipes from my mother, recipes from my grandmother whom I never knew, from my great-aunt, from my paternal grandmother, recipes from my first boyfriend’s mother…

All that female otherness remained; it was largely done by women. But that’s all changing — more and more men are cooking. In fact, I also have recipes from my grandfather and his famous rice pudding!

That’s what’s great about your books, they’re not too gendered…

No, that’s true, that drives me crazy. As for me, I’m very busy; I have a child, and I don’t want to spend even an hour a day in the kitchen.

What I offer and what I talk about is easy-to-make cooking—meals you can prepare the day before, or where you use leftovers to make something very quickly, very well, very tasty! I don’t want to spend the whole day on it!

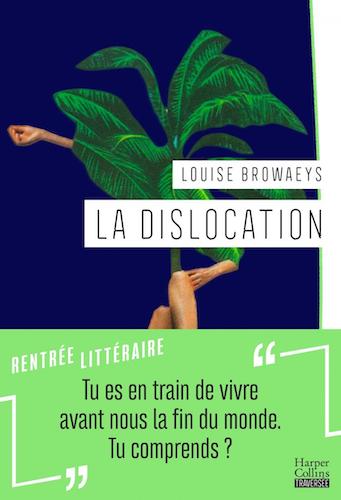

You’re also publishing this fall your first novel with HarperCollins, La dislocation, described as an ‘eco-feminist fable’. For you, how are these two struggles, ecology and feminism, connected?

That’s a broad and delicate question. There are several eco-feminisms and a plurality of ways of being eco-feminist. It’s quite difficult to talk about it like that, theoretically.

Let’s say it’s about bringing these two struggles, ecology and feminism, closer together, by drawing a parallel between the oppression women have suffered over the centuries and the oppression and violence inflicted on the planet and the Earth.

There is the absolutely fascinating thought of Françoise D’Eaubonne, who is a French philosopher we have almost forgotten. She says that it all begins in the Neolithic, when men took control of both soil fertility and women’s fertility. It is from that moment that we enter ten thousand years of capitalism, domination, appropriation, and violence.

What also interests me is the concept of ‘reappropriation’, with the Reclaim movement in the United States, for example, which Emilie Hache notably discusses in her collection of ecofeminist texts titled [Reclaim]. How are women today reclaiming feminism and the way of being a woman? They say: now it’s us who will decide what we want, and we will reconnect to our own inner power.

How to break free from everything that has been projected onto us, how we reclaim a way of being a woman, a feminist, and a human on earth. And besides, this concerns men just as much. The underlying issue is more about how each man and each woman cultivate within themselves both the masculine and the feminine principles and how they come together in love. That’s why it concerns both men and women. How, as a woman, will I cultivate my masculine principle in order to better welcome the feminine principle?

You’re finishing a second novel — is it also written from an ecological perspective?

I don’t really have a message in my novels, and that’s actually what’s liberating compared with writing essays, which is more cerebral and didactic. The novel is written with the heart and the body. You are really in freedom and in nuance. You can even campaign against yourself through the diversity of your characters’ voices.

But it’s true that I can’t help but set scenes and raise questions related to ecology.

What are your upcoming projects?

I started another project, which consists of fragments; it’s a project more connected to poetry that I called “Verdures”. This month Rustica is also publishing a large collective book on autonomy to which I contributed, in the “autonomy at work” section.

And I want to write a book about sex and love. It’s a big topic; I want to do it justice, take the time, and go out to collect testimonies!

Portrait © Matthieu Brillard